Empowering Students to Explore: A Journey of Curiosity and Creativity

This blog post was written by Riana Fisher, a middle school science teacher at Sacred Heart School in Washington, DC.

As educators, we have the privilege and responsibility to guide our students towards a deeper understanding of the world around us. I believe that exposing students to scientific concepts through a diverse array of lenses and respecting and amplifying our students’ voices, ideas, and curiosities can lead to remarkable educational opportunities.

Two years ago, my sixth grade students and I began to explore human impact on the environment. After we had explored the science behind global warming, pollution, and waste, our then-Arts Integration Coach Kristen Kullberg encouraged me to look at these ideas through an artistic lens as well, and recommended we examine some pieces by contemporary artist Alexis Rockman. We chose two paintings by Rockman: Gowanus and Manifest Destiny. Gowanus is a large-scale painting that depicts a polluted Brooklyn waterway, highlighting the effects of human activity on the environment. Manifest Destiny (also a large-scale painting) portrays a dystopian vision of a future where humans have irreversibly altered the environment due to climate change.

Manifest Destiny, Alexis Rockman, 2004. Smithsonian American Art Museum Collection.

Gowanus, by Alexis Rockman, 2013. Artist’s Collection.

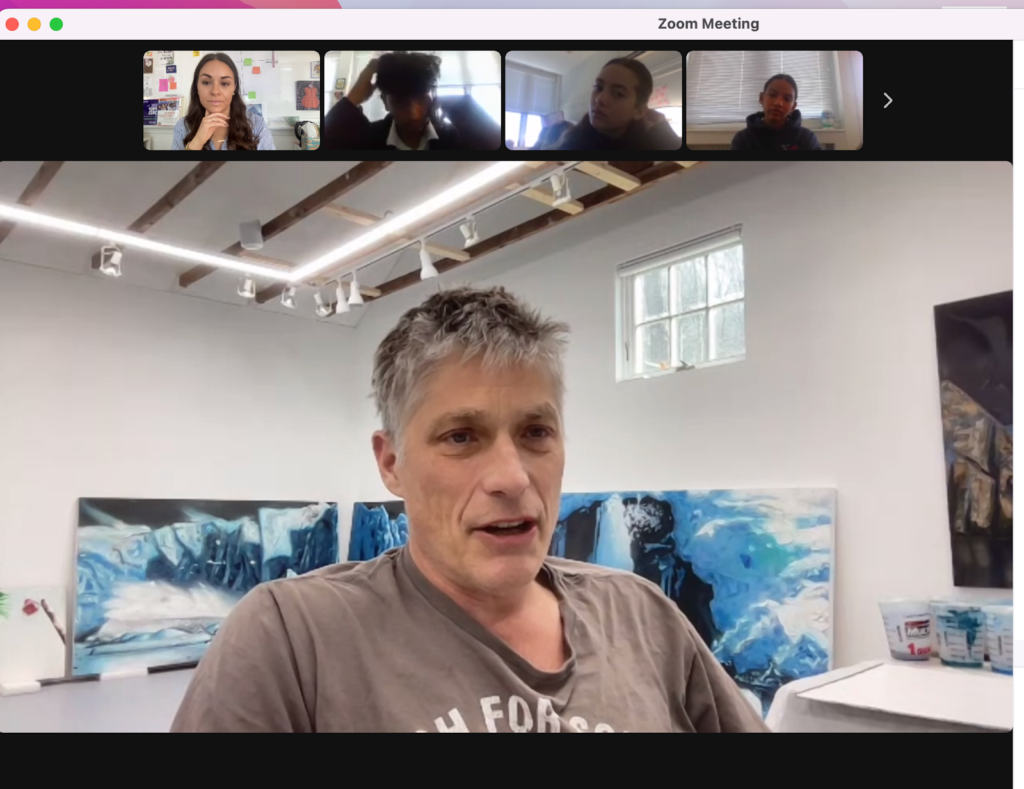

Our exploration of these paintings led to a unique opportunity. One of my students suggested a long-shot idea: Let’s reach out to Alexis Rockman to see if we could ask him questions and talk to him about his paintings. We were thrilled when Rockman responded almost immediately and was excited to meet with us. During the meeting, my students asked questions such as, “What message do you hope people get from seeing these?” and “Where did you come up with the ideas for your paintings?”

Fast forward to this year – this same group of students, now eighth graders, visited the National Portrait Gallery on an art field trip, and we happened to walk by Manifest Destiny (the painting is part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s collection, which shares its building with the National Portrait Gallery). My students were excited to see it in person, and we immediately scheduled another field trip to look more closely at it. We also reached out to Rockman to see if he would be able to meet with us once again.

To prepare, we reflected on our thinking from two years earlier–specifically, on how much our curiosities and thinking had changed since then. One student mentioned missing a lot of the details back in sixth grade, while another realized the questions being asked were more surface-level. A few students also noted that they were more curious back then about the techniques the artist used, rather than the messages he was trying to convey.

After sharing some observations and thoughts with each other, we discussed our new curiosities about the painting. My students were really intrigued this time around by the title of the painting, so we decided to dive into the concept of Manifest Destiny. This led us to explore American expansion in the 19th century, the coining of the phrase, and the myriad ways this policy impacted Native American people. Eventually, the discussion led us to the painting American Progress by John Gast, which depicts the idea of manifest destiny as it was imagined in the 19th century, with a goddess-like figure representing the expansion of the United States westward, bringing “civilization” and technology with her. We eventually placed American Progress and Manifest Destiny side by side and considered what truths were being revealed and what messages the artists might be trying to convey in both paintings.

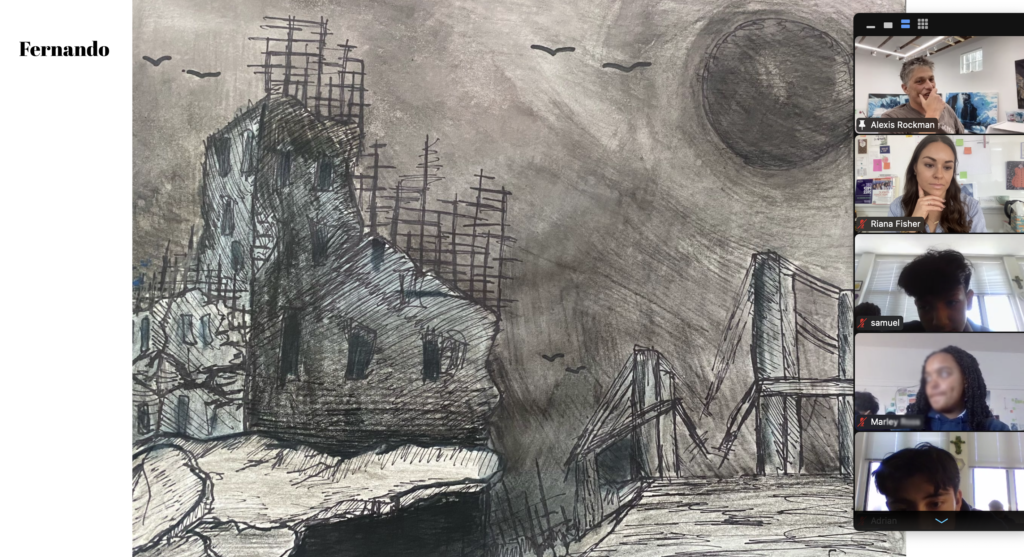

When it came time to brainstorm questions for our meeting with Rockman, I was blown away by the caliber of questions my students came up with: “What do you do in your own life to be environmentally friendly and sustainable, and what do you think we can do better as individuals?” and “Do you think there are any other ways that a manifest destiny mindset still impacts us even if we don’t realize it?” My students also suggested we make our own works of art inspired by the title Manifest Destiny that show our visions of the future and humans’ impact on our planet. They were so proud to share their thoughtfully created pieces with Rockman himself, hear his feedback, and know that they had a hand in creating this special learning opportunity. I have seen these experiences empower my students to interact with people outside the school, reach out to experts, and share their learning with the people who have inspired them.

This experience has reinforced my belief that our students need to be co-creators in the classroom. Respecting their ideas and trusting them to be a partner in their learning led to a remarkable educational opportunity that I believe we would have missed otherwise. If I hadn’t followed up on their suggestion in sixth grade to reach out to Rockman, we would have never been in contact. If I hadn’t been inspired by their excitement that day in the National Portrait Gallery then we wouldn’t have gone back to see the painting again. If I hadn’t looked at their thinking closely and listened to their conversations carefully I wouldn’t have known in which direction to take our learning. I think, as educators, we need to consistently act like detectives or investigators of our students – always listening and observing, and using what we discover to guide our learning.