Stepping into Our Power: Student, Teacher, and Community Voice in the John R. Lewis Leadership Program

The John R. Lewis Leadership Program fosters meaningful, hands-on learning about leadership, justice, service, and advocacy for all Lewis High School students (Fairfax County Public Schools). It is a new program in its first year of design and implementation. The Lewis Leadership Program exists because of student- and community-led advocacy that began with efforts to rename the school to honor John Lewis, and extended to calls for a leadership program connecting students to John Lewis’s life and legacy.

This group of stakeholders designed an innovative model that includes concept-based learning in core classes; a rich menu of outside-the-classroom experiences including guest speakers, field trips, and service learning opportunities; and original courses and internships for students who choose more sustained engagement. Since July 2022, a team of school-based and central office staff members, Lewis High School student leaders, teachers, and community partners has begun building the Lewis Leadership Program together.

What becomes possible in our world when students have real power in our schools? How can we build a program that enacts John Lewis’s democratic values of human dignity and equality? How can we ensure that this program is led by the people it serves?

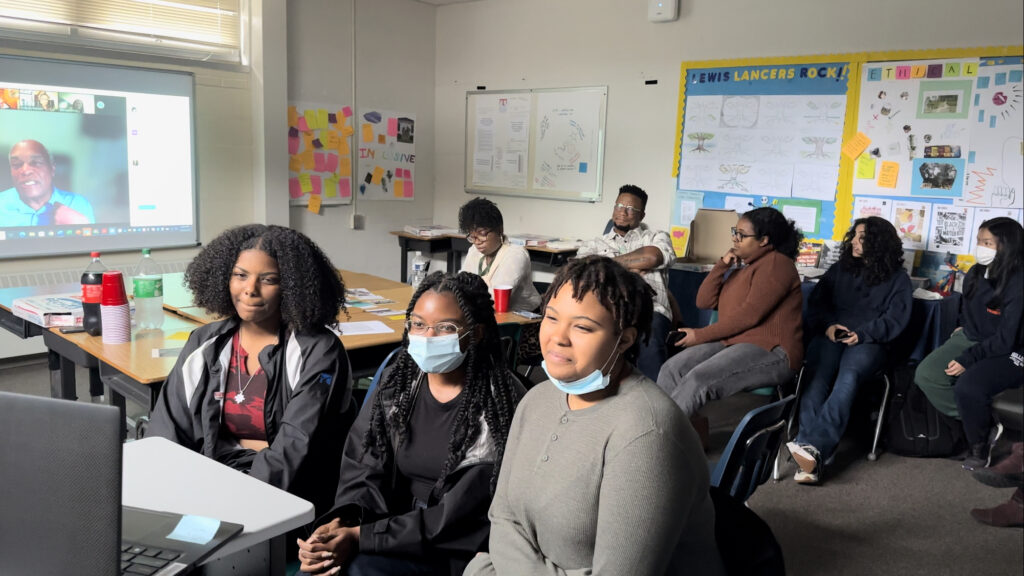

These questions guide our work building the John R. Lewis Leadership Program. Asking these questions connects us to the legacy of our school’s namesake, who understood education’s transformative power. At the beginning of this school year, civil rights activists Courtland Cox, Judy Richardson, and Maisha Moses taught our students and staff about the Freedom Schools built by John Lewis’s fellow organizers in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). They helped us imagine schools designed to foster civic agency through relevant and experiential learning. As we take our first steps toward sustained and authentic student, staff, and community collaboration, we draw inspiration from the many teachers – broadly conceived, past and present – who connect education with freedom.

Our story is at its very beginning; we are taking small steps that everyday bring us closer to big possibilities. We share our story-in-progress here through three voices: student, administrator, and teacher.

Caption: Civil Rights organizer Courtland Cox (on the screen) advises Lewis High School students who ask what he would tell a young person who wants to stand up for justice and get in “good trouble” – October 3, 2022.

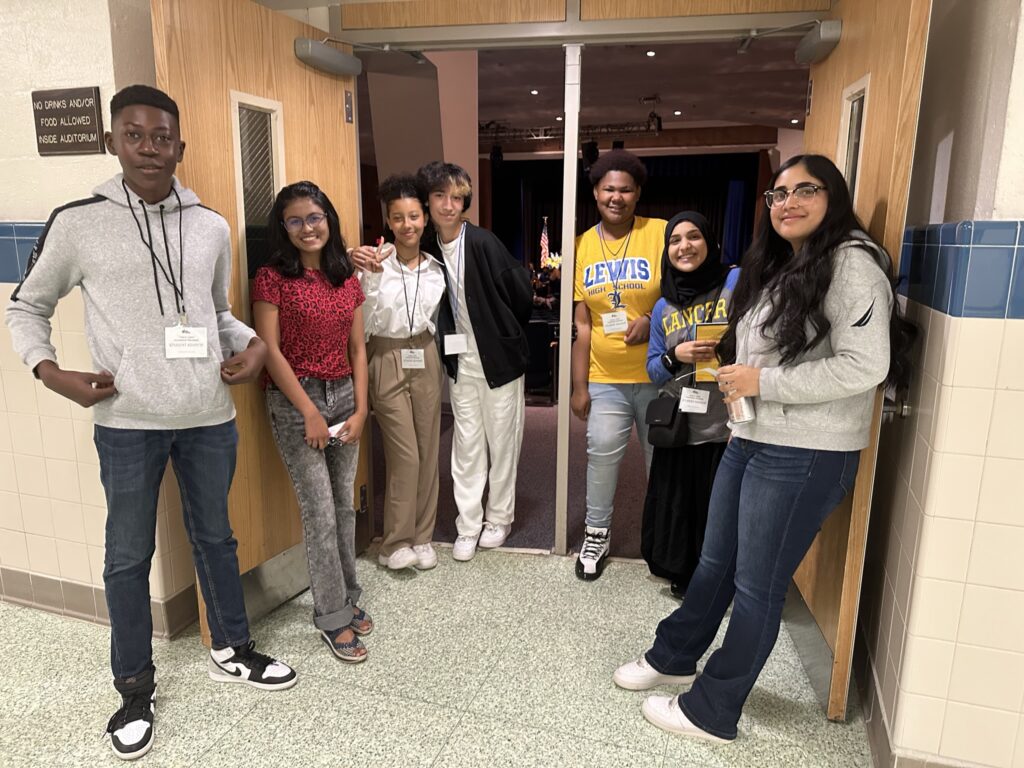

Michelle Olivar, 12th grade, Student Ambassador, John R. Lewis Leadership Program

When I first found out about the Lewis Leadership Program, I didn’t really know what it was or what was the purpose behind it. I was only there because I found it useful to attend instead of doing nothing with such a short class schedule. What I didn’t realize was that I’d come to love the program more than just being there for free time. Becoming a Student Ambassador was my first official role. Student Ambassadors have to attend five Lewis Leadership Program events, complete an interview with Dr. March about our experiences and hopes as leaders, and help represent the program to our peers and the community. As I got more involved, it gave me a sense of leadership to help others that were new or current in the program to be able to get our voice out there.

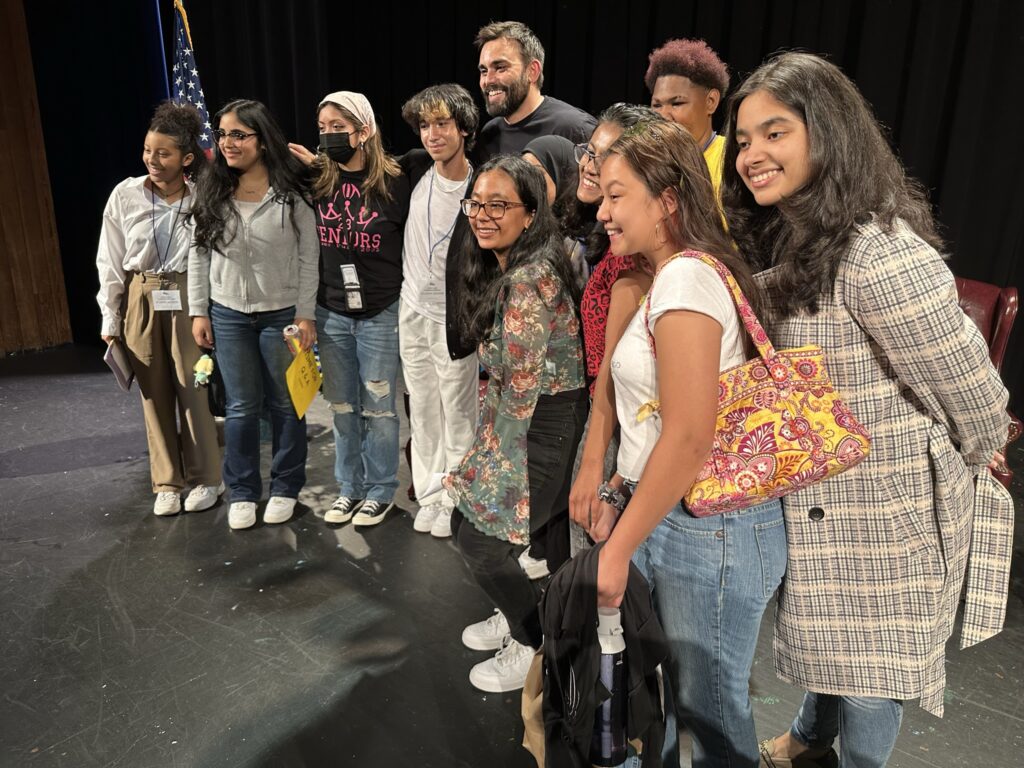

I had many important experiences throughout the program: meeting John Lewis’s former Digital Director and Policy Advisor Andrew Aydin and showing him around the school, looking at objects from the ¡Presente! exhibit with Natalia Febo from the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Latino, attending the John R. Lewis Leadership Program Reception where I got the honor of meeting his brother, Henry Lewis, and recently, my favorite one, taking part in student-led professional learning for teachers. There are many different ways our student voices can matter. I am learning how to use mine to make an impact on something I care about and to help the people around me.

Caption: Michelle (third from left) and a group of Lewis High School students pose with Andrew Aydin – September 27, 2022.

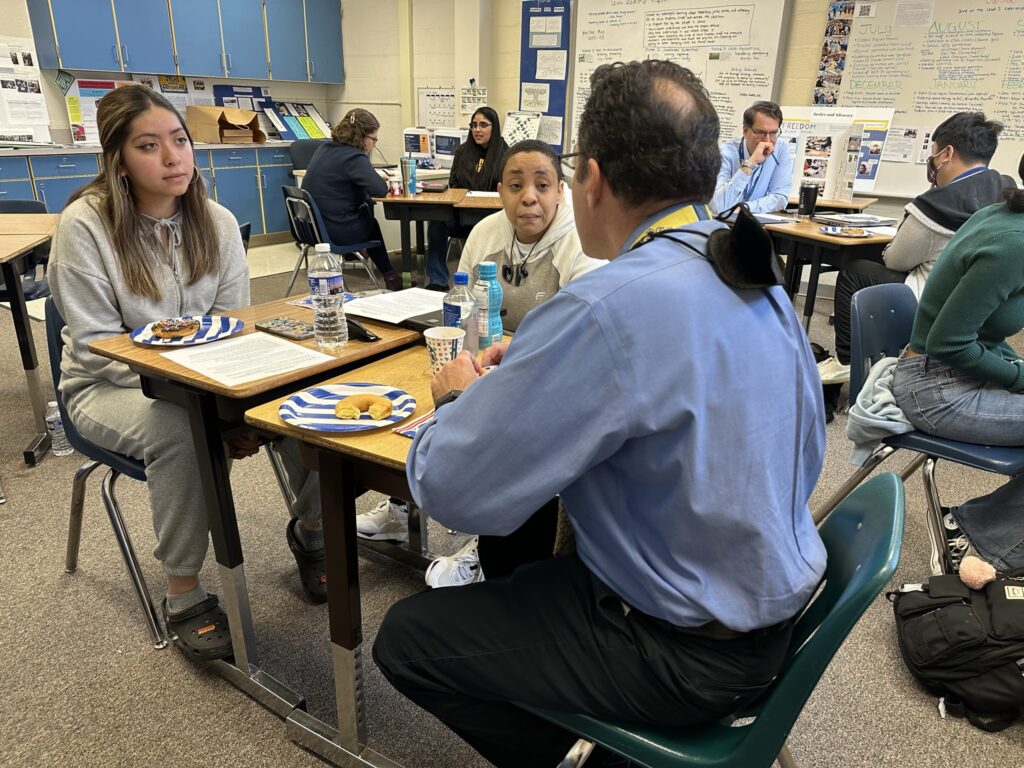

When having the student-led professional learning event a few weeks ago, it was an amazing way of expressing my voice and others’ on how we felt about today’s community and generation. Not only did the teachers who I talked with, Mr. Giblin and Ms. Hill, listen to what I had to say, but they understood my struggles and perspective and made me feel valued and actually heard. I got to listen as well to both of them when they shared their experiences as students and some of the struggles they have been through. As I listened to them, it made me realize that a student and a teacher aren’t that different, despite what others may say or seem to notice. In those 22 minutes of conversation, it connected us somehow with comparing similarities and differences as an old and new generation. It made the bond I already had with one of the teachers become stronger as I finally got to know them not just as a teacher, but as a person, an individual.

Caption: Michelle engages in a dialogical interview with two teachers as part of student-led professional learning – November 10, 2022.

As I reflect as a Student Ambassador on what part I have in the Lewis Leadership Program, it’s clearer than crystal that it involves me, as a senior, helping my peers figure out what they care about in terms of change in political, environmental, or even in mental health–whatever issues matter to them. I want to represent all students who believe in something but aren’t sure what to do about it. I want them to be able to have a voice, feel the importance of what is on their mind, and have that sense of feeling at home within the Lewis Leadership Program, just like me. I want them to have the sense of belonging somewhere that takes opinions and differences. No matter the backgrounds we each contain, we share each other’s pains and hopes like a family. This is what I see as my part in the program and to be able to keep up with it even after graduation. I hope to make changes, view things differently than how I would have before, and learn more along the way.

Editor’s Note: You can view the student-teachers co-created dialogical interview protocol for the student-led professional learning event mentioned by Michelle HERE.

Deborah March, John R. Lewis Leadership Program Manager, FCPS Office of Curriculum and Instruction

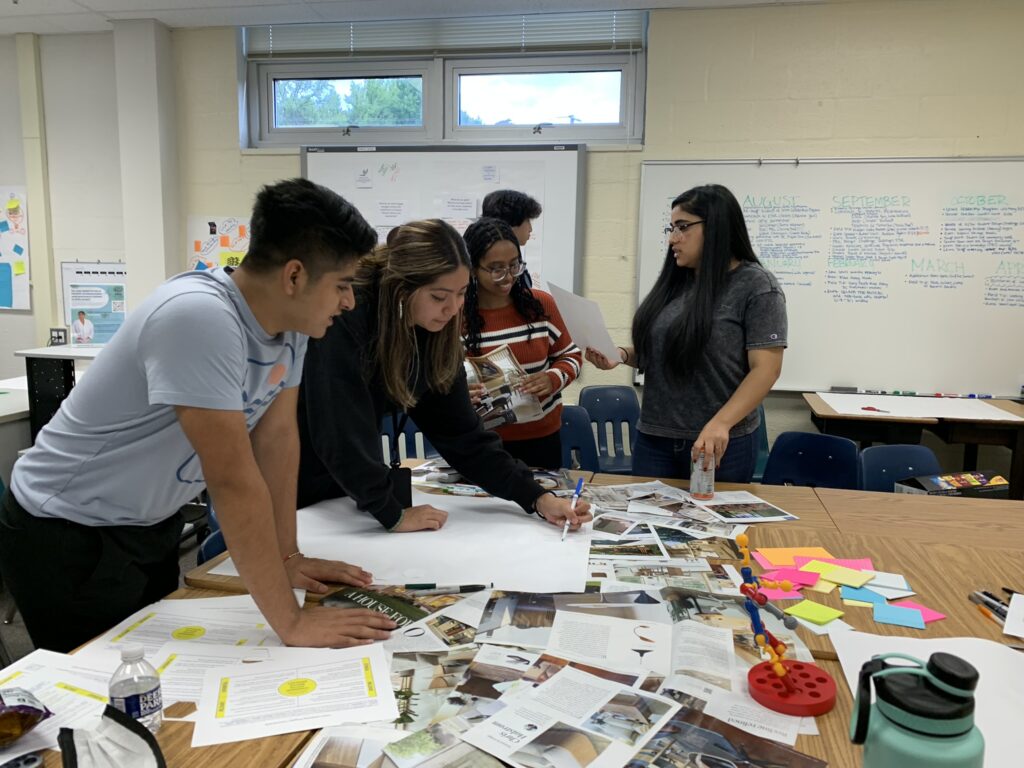

I’ll begin my part of this story the way my Project Zero journey began: with a thinking routine. Here are four photos of the first few months of the Lewis Leadership Program.

- See: What do you notice?

- Think: What thoughts do you have?

- Me: How are you connected?

- We: What are some connections to bigger stories about the world and our place in it?

I value “see-think-me-we” for what it tells learners: you belong, and your voice matters. Your ideas and experiences are important, and we invite you to draw on them to help shape what we are doing together. You have a voice in our community and in the world. These, to me, are the necessary conditions for fostering civic agency, and are at the heart of what we are trying to do at the John R. Lewis Leadership Program.

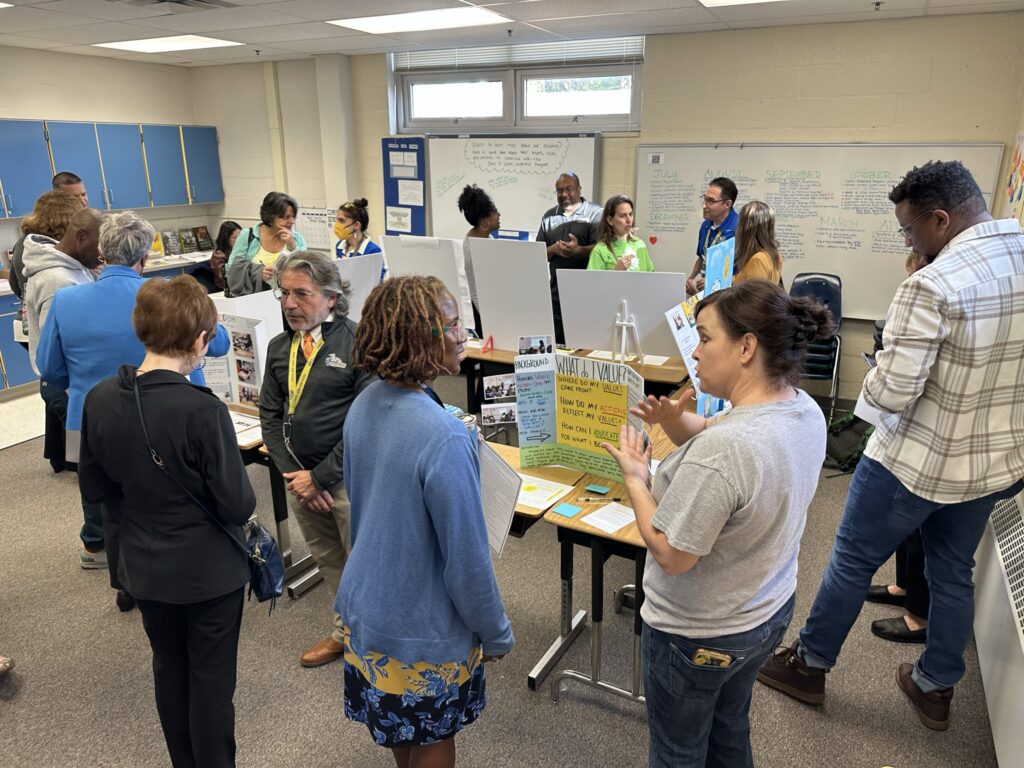

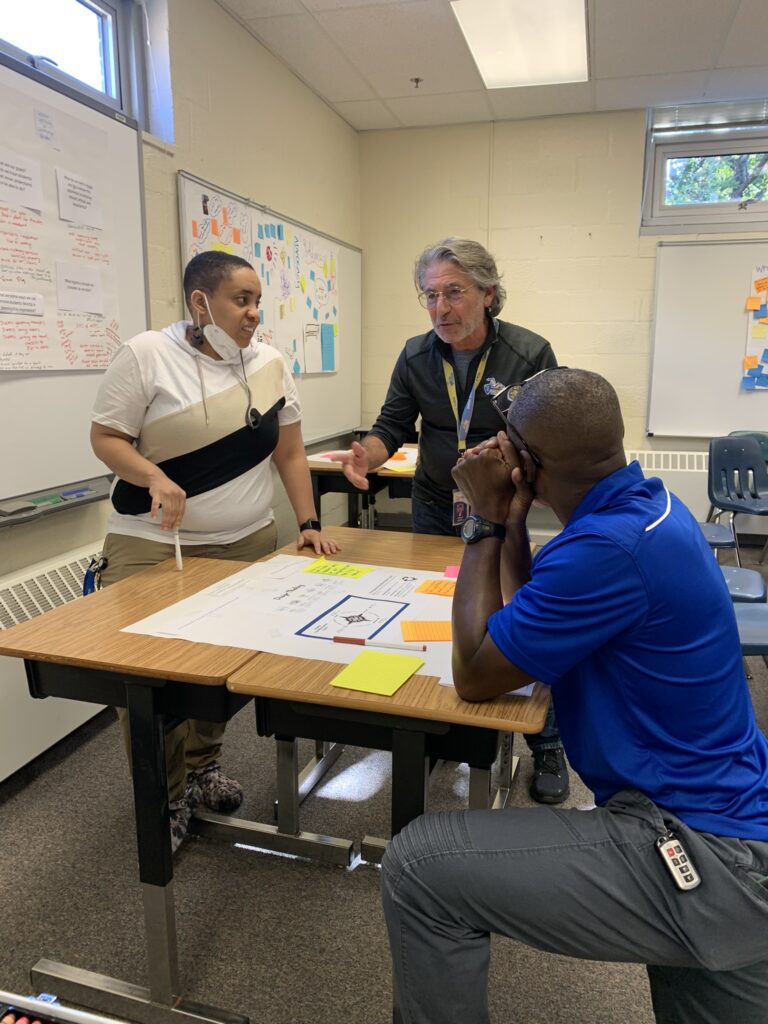

When I look at these photos, I see civic engagement. I see our students, staff, and community partners working together to make a difference. In these photos, we are building structures that foster voice and belonging, like the Student Board of Advisors that meets each week to help me design the program, elevating the perspectives of students traditionally excluded from enrichment and leadership opportunities. We are creating processes that prioritize agency and innovation, like the design cycles and “change ideas” our teacher leader team undertakes each quarter. We are offering project-based learning experiences to any student who shows up, so that all Lewis students can participate in building the program. (The first is a design challenge to make our program room inclusive and empowering for all students, using “Messages-Choices- Impacts” to anchor our design work). We are covering our walls in photos and artifacts to celebrate our community and its learning, and to invite anyone who visits our program room into our story of change.

If you are hearing echoes of WISSIT in this, it’s no accident. The community-building and co-creation at the center of WISSIT Learning Groups; the sense of agency that springs from sustained experiences of making, playing, inquiry, and arts immersion; the critical sensitivity to design that connects us to our power and responsibility to transform systems–these are all aspects of WISSIT I am working alongside staff and students to recreate at Lewis.

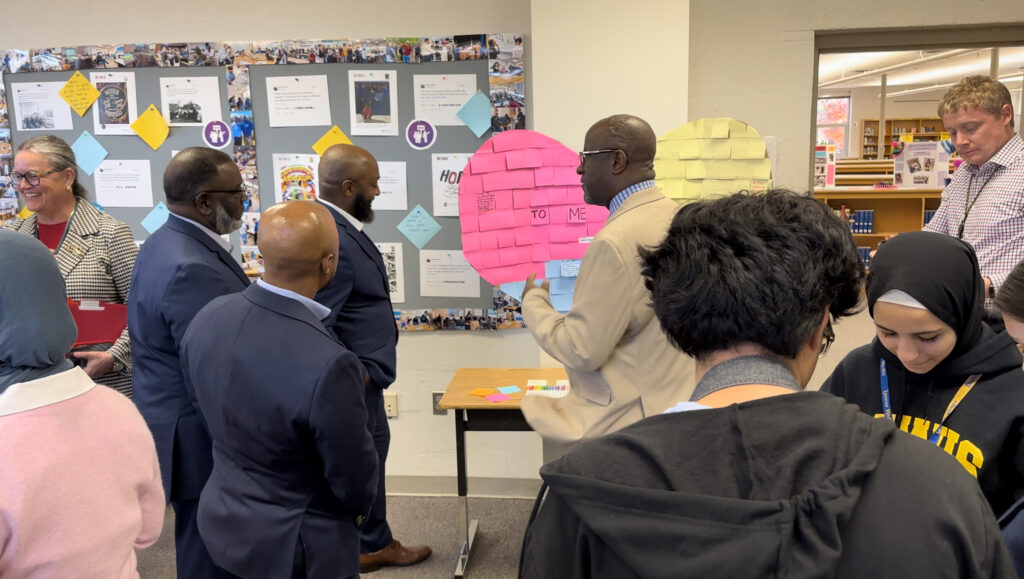

I draw everyday on what WISSIT taught me about the power of documentation. My messy journal and imperfect exhibitions taught me what it feels like to shape and share my story of learning in a personally meaningful way. The walls of my WISSIT 2022 learning group room displayed the power of a community to tell a shared story about its collective learning journey, and to signal its commitment to thinking. And when Jim Reese shared our tweets and photos in a morning plenary (maybe my proudest, nerdiest PD moment!), I learned anew the power of leaders to affirm learners’ inherent value and belonging. Every week at Lewis, our students bring their friends into our program room to point out photos of themselves or to show their posters and prototypes on the walls. Our teachers bring their students and colleagues to see their exhibitions of learning. Documentation helps us democratize meaning-making: the Lewis community can visit the program room, interpret the artifacts on their own terms, ask questions of our student ambassadors and teacher leaders, and contribute to our program’s story by sharing their thinking, for example, on our “Three Whys” heart near the door.

The prompts on this heart ask: Why does the John R. Lewis Leadership Program matter to me? Why does it matter to my community? Why does it matter to the world?

We hope you will visit and tell us.

Caption: Lewis High School Principal Alfonso Smith shows members of John R. Lewis’s family

the “Three Whys” heart that any visitors to the program room may write on: “Why does the Lewis Leadership Program

matter to me, my community, and the world?”

Corey Illes, Social Studies Teacher and Lewis Leadership Program Teacher Leader

When the idea of a leadership program was first introduced to me, I have to admit that I was skeptical. Is this really what our school needs? Is it something that our students asked for? How are we going to effectively integrate this program into a school that is already overflowing with programs to support our diverse population? I have been at this school for 25 years, and I have unfortunately seen many programs come and go, initiatives peak in the fall and disappear by the spring, and a master schedule become unmanageable under the weight of too many offerings. My thinking began to change with a comment that I overheard during one of the initial meetings of the leadership team this past summer. It was essentially that changing the name of our school to John R. Lewis High School was not an end in itself, but rather a beginning and an opportunity for a transformational change of how we see ourselves as educators and as students in this school.

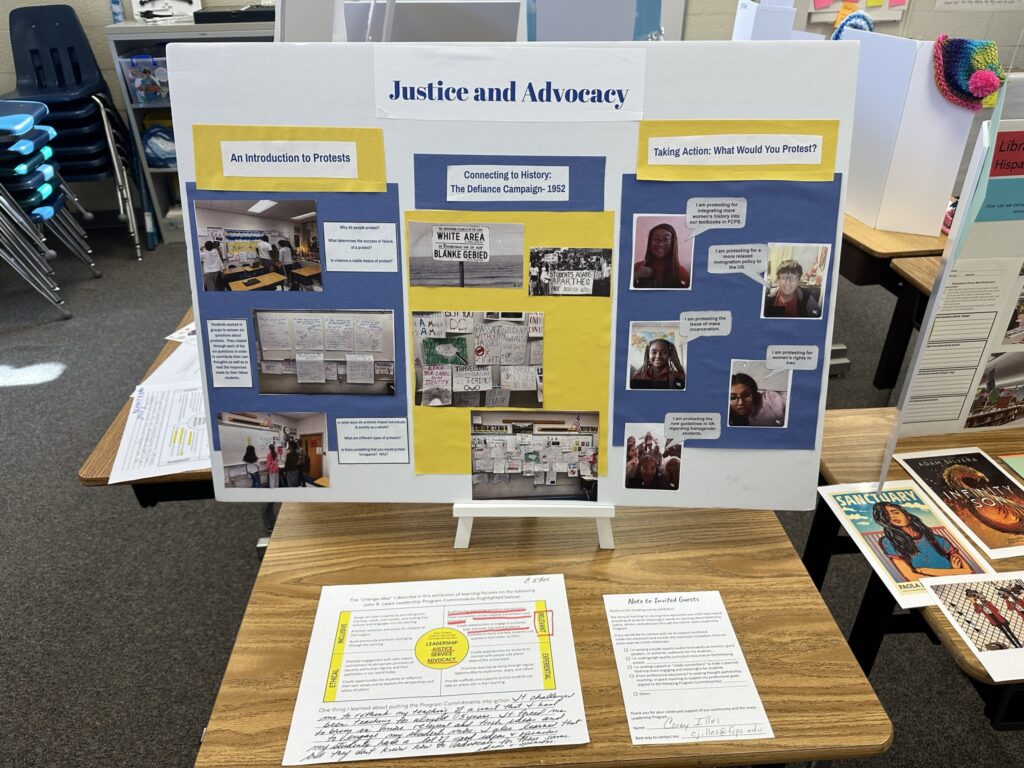

The Lewis Leadership Program has a teacher leadership team of ten teachers and staff members. We meet every other morning during the first block to explore together what this program means for everyday teaching and learning at our school. Our first major “assignment” was to incorporate a “change idea” based on one the four key concepts of the Lewis Leadership program into our classroom: leadership, justice, service, and advocacy.

Captions (left to right): (1) Nine of the members of the Lewis Leadership Program Teacher Leadership team

(2) Lewis Leadership Program teacher leaders at a typical Period 1 team meeting

Caption: Lewis Leadership Program teacher leaders engaged in site-based learning in Springfield exploring the question “What shapes our story of a community?” Here, we are at a community garden, on our way to lunch at a favorite local restaurant.

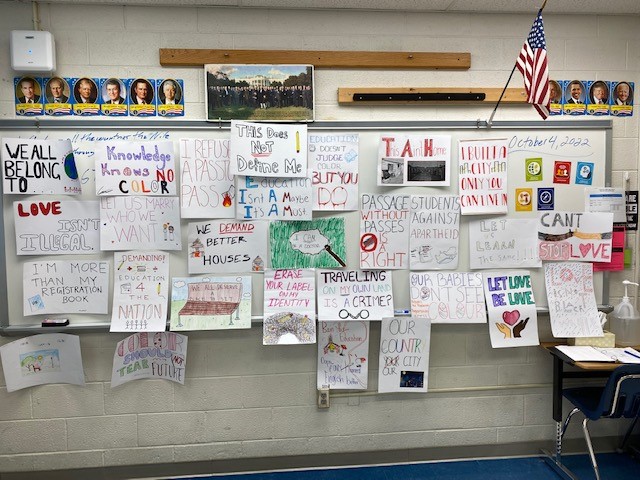

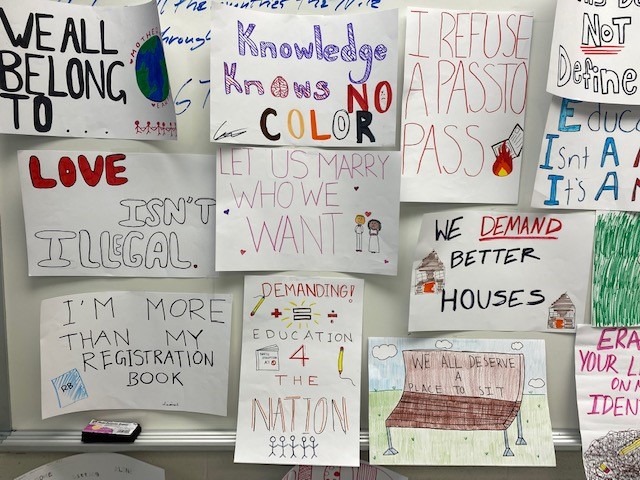

For my change idea, I decided to redesign the way I teach one of the prescribed subjects for our Paper 1 exam in my IB 20th Century Topics class: “Rights and Protest.” We study the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, and I felt that this would be the perfect topic in which to implement my change idea. I wanted to see if it was possible to make this lesson more relevant by giving students the chance to make connections and share what they know right from the start. We started with a Project Zero thinking routine called a “chalk talk.” Each poster posed a question: Why do people protest? What are different kinds of protests? Is violence ever a valid means of protest? Have you ever protested anything? The chalk talk was a small change, but it caused me to rethink my teaching of a unit I had been teaching for almost five years. Students’ responses showed me that they bring a lot of good ideas and important perspectives.

Caption: Students designed these protest signs to demonstrate

their learning about Apartheid in Corey Illes’s IB Topics class

The posters showed me what students already knew and cared about, and they also helped me find opportunities to deepen students’ understanding. I noticed that students shared a lot about their knowledge of protests and whether violence was a valid means of protest or not, but when it came to how to protest for or against something, they wrote far less, and seemed to have less knowledge to draw on. It was not that I was surprised, but it did afford me an opportunity to incorporate two of the key commitments of the Lewis Leadership program into my teaching of the unit: justice and advocacy.

I asked students to choose one issue that they cared about and then explain how they would go about advocating for their position on this issue in a two-minute Flipgrid video. It was not enough for students to say “I would go out and march” or “I would write a letter”. Students had to be very specific. Who would they write the letter/email to? What would it say? What organization would they contact or possibly join? What legislation could they support? This really challenged students to look into their issue more deeply and to educate themselves on the “how” part of advocating for something. It was important that my students had the freedom and support to decide what they value, what change they hoped to see, and what method of advocacy felt right to them.

Students chose a variety of interesting, relevant, and important topics to voice their opinions on. Some of the topics that were discussed included the treatment of women in Iran, worker’s rights in Bangladesh, the recent Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, and Virginia’s policies regarding LGBTQ+ student’s rights in school. What was most encouraging about their testimonials was that they were able to include the “who” and the “how” of their protest. They shared specific examples of organizations that they could connect with. It was a small, but important step in the development of how they could advocate for justice on a wider scale.

It is clear to me now that one important aspect of the Lewis Leadership program is going to be focused on teaching our students how to advocate for themselves not only as citizens of the world, but as individuals in their own communities, and it’s going to start in their own classrooms. This is an essential life skill that all of our students need in order to be successful and responsible citizens. My initial skepticism has quickly faded away as I continue to work with the Lewis Leadership team to unearth the many ways justice and advocacy can be blended into our classroom teaching practices.

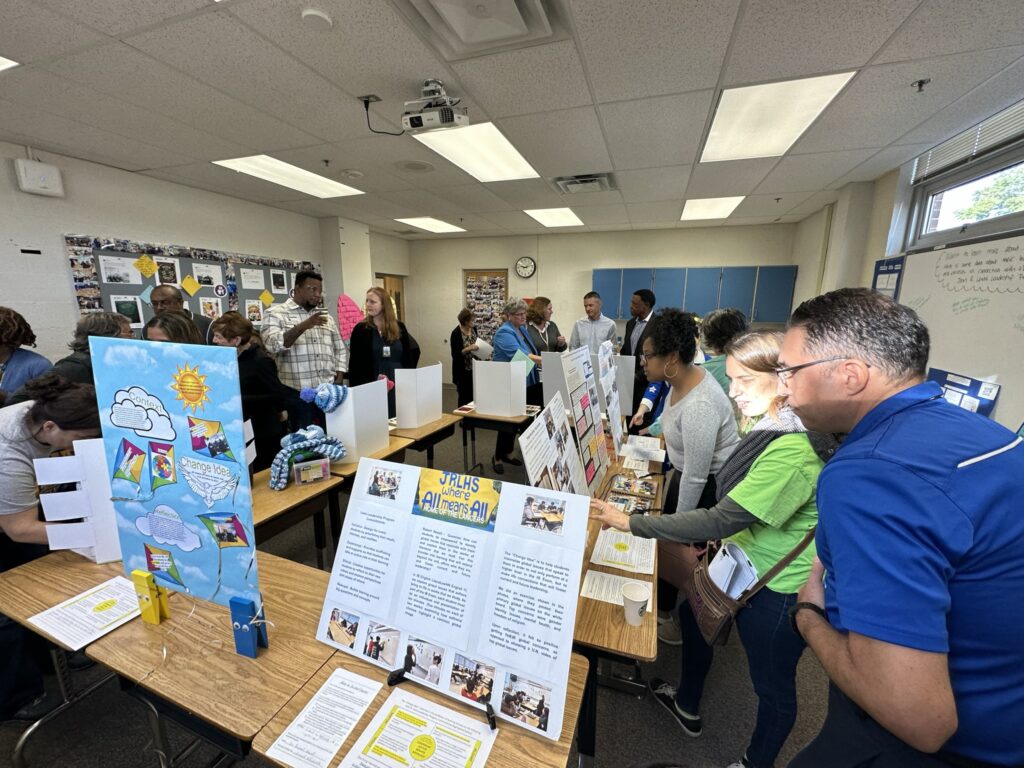

Captions (left to right): (1) Corey Illes’s exhibition of learning

(2) Lewis staff, FCPS staff, and community partners at the exhibition