Teaching with Museum Resources

Sean Felix

Middle School Humanities Teacher

Edmund Burke School

Teaching using art is one of the greatest assets for student learning. Artworks can provide concrete visual examples that enhance a given lesson, or push thinking beyond the literal. Teaching about historical eras and literature using visual aids allows students to create empathetic bonds with historical figures and stories they read. These bonds support learning by providing not only an intellectual understanding but also an emotional connection to the subject.

My name is Sean Felix, and I am an independent school humanities educator at the Edmund Burke School in Washington, DC. Art is a vital part of my 6th grade English/history pedagogy. I’ve used paintings, photographs, and sculptures, among many other art forms, to enhance my students’ understanding, both in the classroom and, when possible, at monuments and in galleries throughout the region. My class has a particular bond with the National Gallery of Art, forged through my years of work with their Summer Institute and through bringing the students to the gallery for their docent-led educational programs and using curricula designed in concert with the education department. My lessons have benefitted greatly from this collaboration.

One recent lesson I conducted using National Gallery of Art resources was for English Language Arts in which I tried to get students to understand the conflict and friendship among characters in the Jerry Spinnelli novel, Crash. In consultation with educators at the National Gallery, I decided to use Edward Hicks’ painting Peaceable Kingdom with my class. The painting, which Hicks created over 60 times, portrays two scenes. In the foreground, on one side, is a scene of wild and domestic animals, some lying down and playing with small children, and, in the background, on the other side, is a scene of a 1682 peace treaty ceremony between Tamanend, leader of the Lenape Indians, and the Quaker colonist William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania.

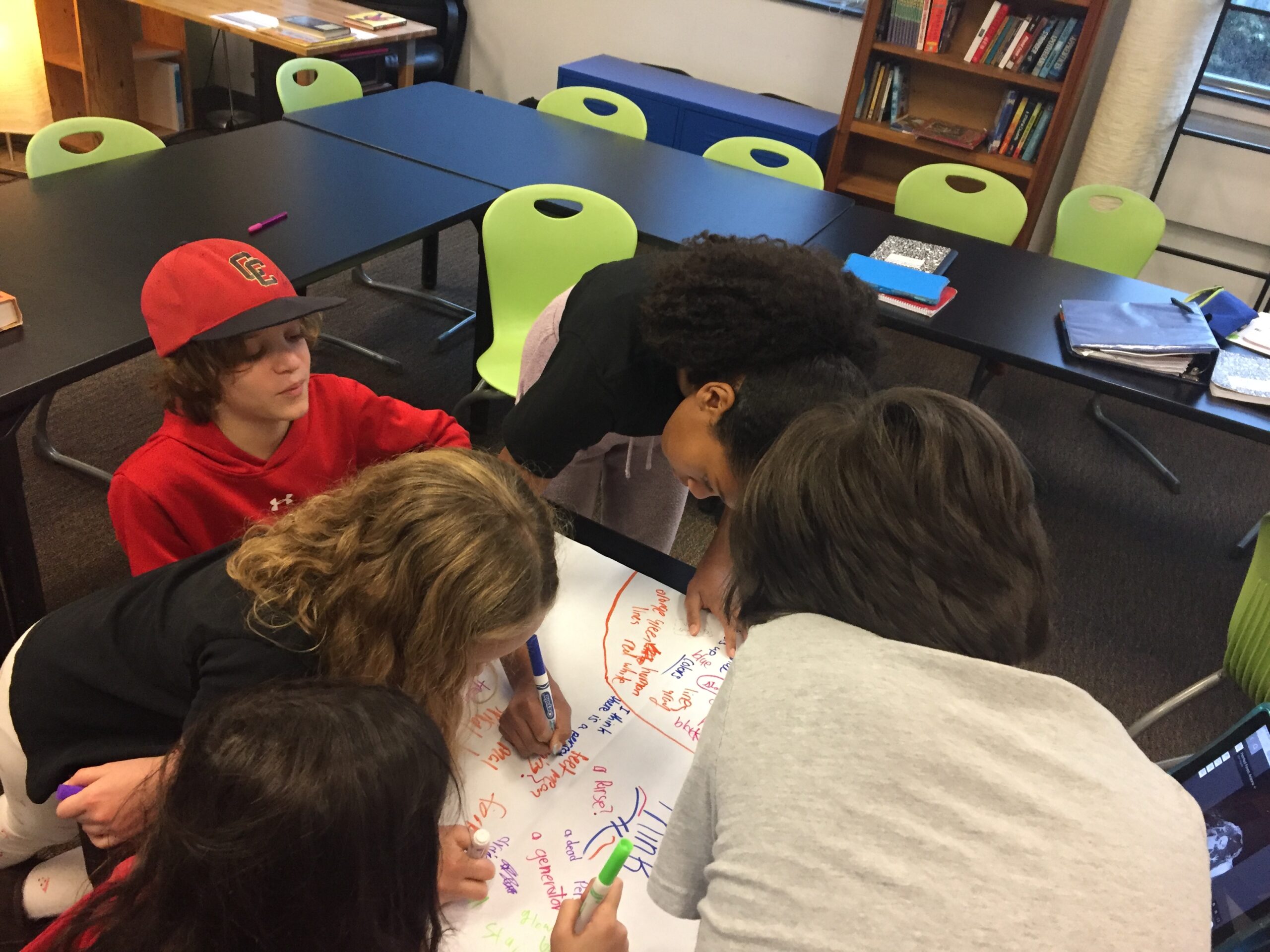

My intention was to explore the painting through three Project Zero Thinking Routines: See-Think-Wonder; Circle of Viewpoints; and What Makes You Say That?. I wanted to see if the students could draw connections beyond a surface reading of both the book and the painting in order to gain deeper insight into the novel’s character relationships. Initially, because of limited educational/personal experience regarding Native American interactions with English colonists and Quakerism, the students struggled to see how each side of the painting related to the other. They gave surface responses, such as “the animals were what the Native Americans ate,” and they saw “animals, and cupid babies, Native Americans, and colonists.”

As the lesson unfolded though, I gave some historical background on Edward Hicks, William Penn, Tamanend, and Quakerism, connecting them to the biblical passage from Isaiah 11: 6-9, which Edward Hicks used as inspiration for the painting:

(6) The wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard will lie down with the goat, the calf and the lion and the yearling together; and a little child will lead them. (7) The cow will feed with the bear, their young will lie down together, and the lion will eat straw like the ox. (8) The infant will play near the cobra’s den, and the young child will put its hand into the viper’s nest. (9) They will neither harm nor destroy on all my holy mountain...

Soon after I gave them this information, the painting and the book exploded to life for them. They connected the Crash characters–Penn Webb and his Quakerism, and Crash and his aggression–to the peace being depicted on both sides of the painting. Looking at the painting again they gave responses like: “Penn always just wanted peace,” and “It’s better to be nice to people than to be mean!” Another student said, “They saw each other as equals.” (William Penn and Tamanend, Crash and Penn Webb), and another, remarking on the relationships between the white settlers and Native Americans and between Crash and Penn, said, “Equality is necessary for peace.” I was amazed by not just how quickly their viewpoints expanded, but also how passionate they were in their reflections on the novel and their lives.

Reading Crash and having students use these Thinking Routines to make their thinking visible in this way also opened more doors of study and exploration: geography, word origin, and history. We started the lesson with Circle of Viewpoints and we ended it as well with the same question: “What is most important to the main characters in the story?” At the end of the novel, Crash says, “And Penn Webb is my best friend.” One of my students in a final reflection on the lesson and the book remarked not just on the book but on the world we live in, saying, “Peace and friendship is [sic] most important. Is Peace possible though? Yes. But not in their (our) lifetime.”

I worked with the National Gallery team on developing this project and presented what happened in my classroom with Peaceable Kingdom during one of their Massive Online Open Courses (MOOC). I have continued working with the NGA, most recently in using Romare Bearden’s Tomorrow I May Be Far Away to teach about the Great Migration and the novel Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, and to teach about migration and refugees using Richard Mosse’s Incoming.

Expressing ourselves through art is fundamental to the human experience. It opens doors of communication to show our thoughts and feelings. Also, it presents opportunities for us to understand complex topics on a deeper level. I hope that my examples show some ways that this can be done, and that some of you might take the opportunity to include art in your classes. Your students will be so thankful for it.

Ellen Rogers

Primary Years Program (PYP) Coordinator

Belvedere Elementary School (FCPS)

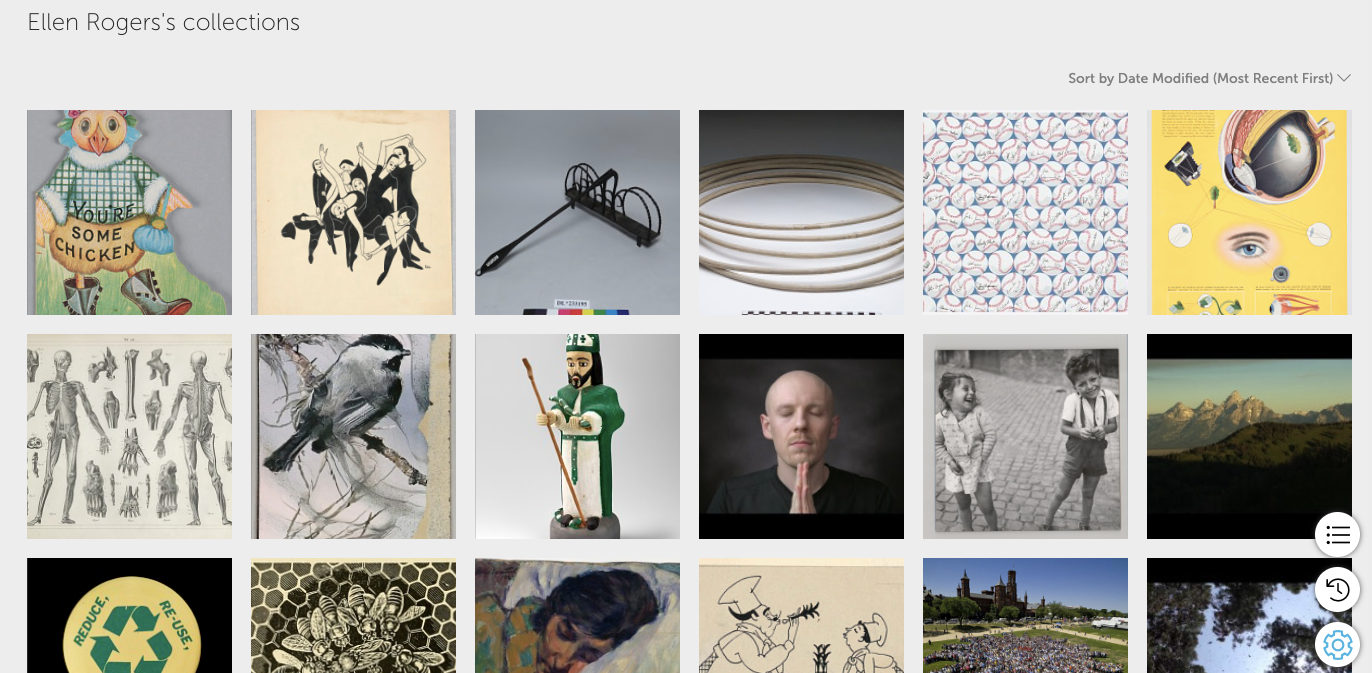

Several years ago I moved to a new grade (4th grade, to be exact) and a new curriculum. I had been attending WISSIT over the summers and was ready to use what I had learned with my students. One person I had met at WISSIT was Tess Porter, the Digital Content Producer at the Smithsonian Office of Educational Technology. She introduced me to the Smithsonian Learning Lab and ways teachers could create their own collections with Smithsonian museum objects. I was struck by what a great opportunity it would be for my students to have agency when looking at important materials around topics we were learning. We are limited in the number of field trips we can take in a year, and the Smithsonian Learning Lab made it possible for my students to interact with museum objects in an intimate way on a monthly basis.

When my year as a classroom teacher began, I started tinkering with using the Learning Lab and creating my own collections. This digital resource made it possible for my students to examine artifacts and objects closely and to have meaningful conversations around what they saw. One of my first collections was about enslaved life in the United States during the 1700s. I wanted the students to spend time really looking and inquiring about the objects and images. The collections provided the perfect focus for thinking routines, and it was amazing to hear and see what my students thought about the objects.

As I started documenting my students’ work with Learning Lab collections, I was asked to join Museums Go Global. This project gathered area educators to create collections that combined thinking routines, museum resources, and global competence. The amazing part about participating in the project was that we got to go to museums and meet with, learn from, and consult with museum educators. I walked away with new strategies and approaches as well as experts to contact. I was shocked to find out that museum educators were willing to curate programs that matched the units of inquiry my students were studying. (A big thank you to Briana Zavadil White, Nathalie Ryan, and Elizabeth Dale-Deines!)

Later, I moved into the PYP (the International Baccalaureate’s Primary Years Program) Coordinator position at my school, which allowed me to use the Learning Lab collections and museum experiences with the whole school. When planning units with grade level teams, I created Learning Lab collections or used museum objects that would drive curiosity and inspire inquiry. This created a culture at our school around using museum objects and raised interest in museum visits.

When the pandemic closed school, I committed to making a Learning Lab collection every day and posting it on Twitter. In doing so, my school community got a chance as families to examine museum resources together and have conversations. My collections were being used by other schools within my school system and beyond.

As students started to return to the building I saw digital collections as a way of bringing joy and levity to students and teachers. The perfect example of this is my collection about cicadas and my school-wide “Wanted” posters for blue-eyed cicadas.

The pandemic changed the way students experienced school, and the digital access to museum resources has evolved into digital museum experiences. This year our first and fourth graders participated in a mindfulness program through the National Asian Art Museum that combined art and yoga. One of our teachers remarked after the program, “The museum educator was so patient and engaged when it came to working with my class! She genuinely wanted to hear what my students were wondering and thinking. It was nice as a teacher to get to observe my students and notice the connections that they were making to things we had learned in class already. And now I have some strategies for talking with my students about art and some yoga moves to use in morning meetings.” We also have had our fifth graders participate in digital programs from the National Museum of the American Indian, and our 4th graders have participated in a program examining portraits of Pocahontas from the National Portrait Gallery.

My big takeaway from all of the museum experiences that I have had over the last few years is to just start trying things out, document what you do, attend trainings when you can, and reach out to museum educators for support.