DCPZ In Action, Vol. VI: Kristen Kullberg

“DCPZ In Action” highlights the many ways in which DCPZ educators are using Project Zero ideas in their practice. We hope that our readers will be inspired to try something new in their own setting. Each of these articles will be posted in a DCPZ newsletter and as a blog on our Professional Development Collaborative website.

In this edition, we hear from Kristen Kullberg, the Making and Design Initiatives Coordinator in Washington International’s middle and upper schools (and formerly an English/Language Arts teacher and Arts Integration Coach at Sacred Heart School of DC). Kullberg is also on the WISSIT Leadership Team.

“Like math, making is a universal language. It’s a way to show what you know and put ideas together. It’s also a way to make friends.” This is what Harry, an eighth grade student, said to me on my very first day as Washington International School’s new Middle and Upper School Making and Design Initiatives Coordinator. I had asked him why having a space like the Design Lab was so important to him and why it might matter to our larger school community. Every day since then, I’ve had the privilege of watching Harry’s insights come to life.

In this new role, my biggest goals are to provide WIS students with two things: arts-based learning experiences that provide different entry points into academic content and a space to demonstrate their understanding in novel and innovative ways. In short, I want every single student to get their hands on and in deep learning and understanding.

So, how does one go about making this happen?! I rely heavily on intentional and open-minded collaboration with my colleagues. Planning with purpose and flexibility is key. The typical arc of planning begins when the classroom teacher reaches out to me with an idea, and we sit down to chat in the Design Lab to establish shared learning outcomes and understanding goals for the students. With understanding goals always as the driving force, together we design maker-centered learning experiences that promote looking closely, uncovering complexities, and finding opportunities to reimagine design as well as the systems around us.

In English Language Arts/Literature, for example, we deepen our understanding of an author’s approach to genre and perspective by identifying and examining the parts, purposes, and complexities of a graphic novel. In Chemistry, we negotiate the complexities of triple bonds using only straws and buttons. In Design Technology, we take apart everyday objects to uncover the hidden design elements inside and use this knowledge to design our own inclusive and culturally responsive toys. In Humanities, we celebrate the engineering feats of the Minoans by creating our own ancient city complete with a functioning water system. In French, we create self-portraits made of found objects to promote language acquisition and to connect with one another as a learning community. And the list goes on! There is no limit to how maker-centered learning can not just bolster academic achievement throughout the disciplines, but also allow learners to navigate and make sense of the curriculum.

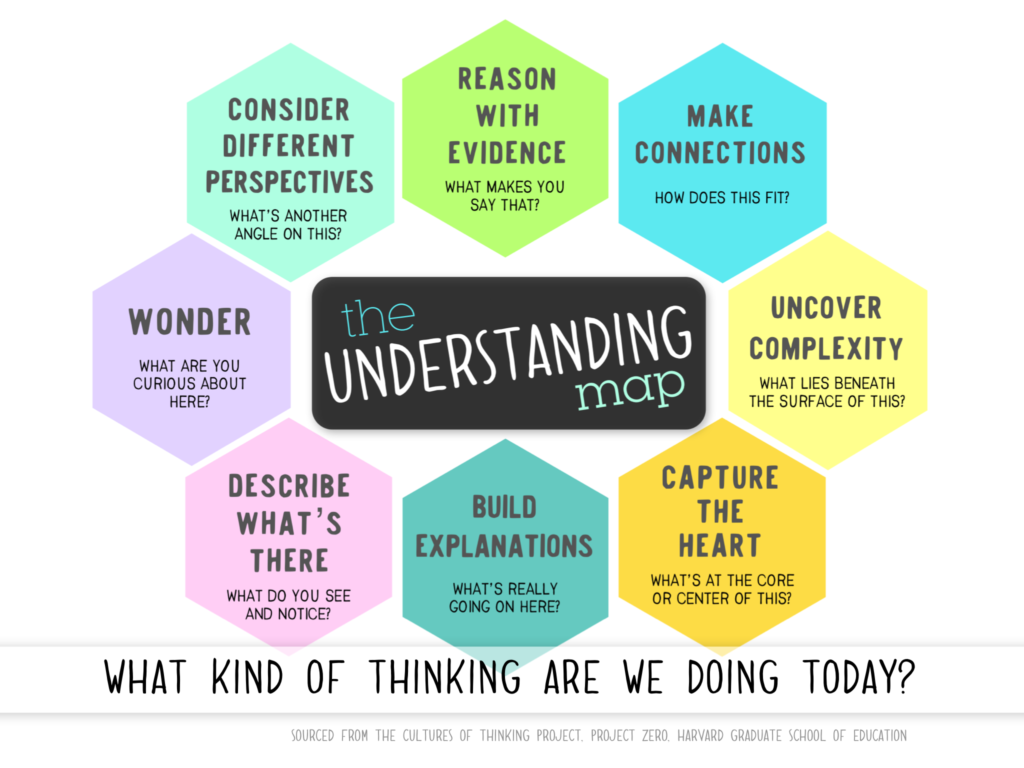

The key to providing a meaningful learning experience in the Design Lab (or anywhere that making is happening) is to ensure that the types of thinking we’re enacting mirror those being nurtured back in the classroom. Just as themes can carry student learning throughout the disciplines, so can thinking dispositions. Reasoning with evidence, making connections, and considering different perspectives shouldn’t only happen in the traditional classroom. Why not give our learners a chance to uncover complexities and build explanations with their hands?

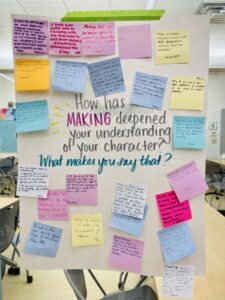

After observing some of her students discuss the different bonds and compounds they were constructing in the Design Lab, Ms. Denney, the upper school chemistry teacher, was elated to hear her learners using target language as well as demonstrating emergent understanding of triple bonds, a topic she hadn’t yet broached with them, but was a natural next step beyond what they were currently learning. The students who explored genre and perspective in their English Literature class reflected on how the act of deconstructing the graphic novel they were reading deepened their understanding of the characters’ emotions as well as the building blocks and tools of effective storytelling.

One student observed, “Being able to rearrange the panels and cut out important parts helped me view the graphic novels in an entirely different way, because I had to think critically about why each of the individual pieces were chosen by the artist to aid the story.” Working together in the Design Lab also gave students opportunities to observe and reflect on each other’s work, with one student noting “When looking at my peers’ work, I learned and thought about their ideas on parts of the graphic novel and what their purpose might have been. They had written what I hadn’t thought about on some of the parts, so this helped me with the purpose aspect of the work.”

Looking through an old accordion journal of mine, I was struck by one page in particular. In the middle of an array of doodles and emergent thoughts and questions, I saw where I had jotted, “The hand doesn’t end at the wrist.” Who spoke this? I honestly can’t remember, but the lasting impact on my practice, and consequently the way I think about learning, has been immeasurable. I take these words as an invitation into maker-centered learning. When students are invited to use their hands in their learning, the mind is liberated in ways I’m just only beginning to understand. As a result, connections are made as complexities are uncovered and wonders bubble up to the surface. Making is simply essential to thinking and learning.

In the end, Harry’s right: Making is a universal language. It transcends disciplines, learning styles, and language barriers. It allows teachers to depart from conventional practices, students to access academic content in innovative ways, and communities to come together; and I count myself as insanely fortunate to provide such a sacred space for our students.